Speak Out! Save Lives.

Use these videos yourself or share with a friend.

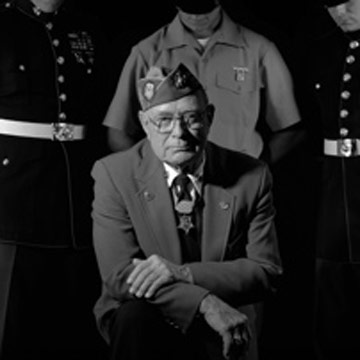

Corporal, U.S. Marine Corps, 21st Marines, 3rd Marine Division

The first time the five foot six, nineteen-year-old Hershel “Woody” Williams tried to join the Marines, in the fall of 1942, he was too short. The second time he tried, a few months later, he wasn’t: The Corps relaxed its height requirements. He immediately enlisted. He was sent to the Pacific with the 3rd Marine Division and placed in a flamethrower/demolition unit.

Williams took part in the invasion of Guam, which seemed horrific—until he was sent to Iwo Jima the following year. The beach area in Guam was clear and relatively undefended, and the Marines could advance into the jungle. At Iwo, all the jungle cover had been blown away, and the beach became a slaughterhouse.

His company was supposed to hit the beach on February 20, 1945, but there were so many Marines stuck on the beachhead that there was no place for them. They finally landed the next day, even though the Marines were still backed up, unable to advance. The island’s volcanic ash was so porous that it was impossible to dig foxholes or create cover, and the Americans, exposed to enemy fire, were taking huge casualties. Williams’ unit had landed with six flamethrower men and had lost them all in two days without advancing more than fifty yards. Morale was plummeting.

On February 23, Williams suddenly heard Marines shouting and firing their weapons in the air. Looking up, he saw that the American flag had been raised on Mount Suribachi. Spurred on by the sight, his company surged forward and finally advanced, crossing the first airfield and assaulting the enemy.

The Japanese defenses were organized around pillboxes of reinforced concrete arranged in pods of three, connected by a system of tunnels. Acting Sergeant Williams saw the American tanks wallowing impotently in the soft volcanic sand. With covering fire from four riflemen, he strapped on a flamethrower and went after the pillboxes. Over the next four hours, he moved through intense enemy fire to assault one Japanese position after another. He climbed on top of one pillbox and stuck the nozzle of his flamethrower through the air vent, killing the soldiers inside and silencing the machine gun. When enemy soldiers from another pillbox fixed their bayonets and charged him, he killed them all with a burst of flame from his weapon. He repeatedly returned to his own lines to get new flamethrowers or pick up satchel charges, which he tossed into the pillboxes he had disabled. Finally, an opening in the Japanese lines was created, enabling the Marines to advance.

When Williams’ company was taken off the line a week and a half later, only seventeen of the 279 men who had hit the beach with the company had not been killed or wounded.

After the battle of Iwo Jima, Williams went back to Guam as part of the Marine force training for the invasion of Japan, which was unnecessary after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On October 5, 1945, he was ordered to Washington to receive the Medal of Honor. The moment President Harry Truman placed it around his neck, he resolved to consider himself the medal’s caretaker for the Marines who didn’t come home from Iwo Jima.

Hershel Williams later became active in his church as a lay minister. He served his fellow recipients and their loved ones as chaplain for many years. He is now chaplain emeritus of the Congressional Medal of Honor Society.