Speak Out! Save Lives.

Use these videos yourself or share with a friend.

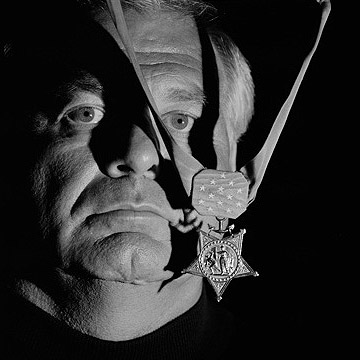

Petty Officer, U.S. Navy, Navy Advisory Group

Although he came from the landlocked hills of South Carolina, the idea of being in the Navy seized Michael Thornton’s boyhood imagination when he saw movies such as The Fighting Sullivan Brothers and Frogmen. He enlisted in the Navy shortly after graduating from high school, went through Underwater Demolition Recruit Training, and became a member of the elite SEALs.

In the fall of 1972, with the U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia winding down, there were only three officers and nine enlisted SEALs left in Vietnam. Thornton was one. Their primary missions were rescuing downed American airmen and doing “sneak and peek” reconnaissance on the North Vietnamese Army’s inexorable advance into the south.

On October 31, a five-man SEAL patrol was ordered to gather intelligence about enemy activity at the Cua Viet River Base. The patrol was made up of three South Vietnamese SEALs, Lieutenant Tom Norris, and Petty Officer Thornton. Both of the Americans were experienced combat veterans. Earlier that spring, in fact, Norris had led a similar team on a heroic mission to rescue a pair of U.S. airmen who had been shot down in enemy territory, an action for which he would be recommended for the Medal of Honor.

Launched in a rubber boat at dusk by a Vietnamese junk, the SEAL patrol paddled toward the beach in the gathering darkness. About a mile offshore, the men left their small boat and swam to shore. Then they moved inland, passing silently beside numerous enemy encampments. They patrolled all through the night, gathering important intelligence. As daybreak approached, seeing no identifiable landmarks, they realized that they had come ashore too far north; in fact, they were in North Vietnam. As they moved back toward the beach, Lieutenant Norris established radio contact with the fleet. However, they were soon spotted by the enemy and began to take heavy fire. More than fifty enemy soldiers attacked, closing to within five yards.

During a five-hour firefight, Thornton was wounded in his back. Norris ordered Thornton and two of the South Vietnamese SEALs to fall back to a sand dune to the north and provide covering fire. Not long after, the Vietnamese SEAL who had stayed behind arrived at Thornton’s position and told him that Norris had been killed. Thornton charged back over five hundred yards of open terrain to Norris. When he got there, he killed two enemy soldiers standing over the lieutenant’s body. He lifted Norris, barely alive and with a shattered skull, and began to run back toward the beach, enemy fire kicking up all around him.

The blast from an incoming round fired by the USS Newport News blew both men into the air. Thornton picked up Norris again and raced for a sand dune and then retreated three hundred yards to the water. As he plunged into the surf, Thornton lashed his life vest to the unconscious officer’s body. When another SEAL was hit in the hip and couldn’t swim, Thornton grabbed him and slowly and painfully swam both men out to sea. Despite his wounds, Thornton swam for more than two hours. All three wounded men were rescued by the same junk that had dropped them off sixteen hours earlier.

On October 15, 1973, Michael Thornton was on his way to the White House to receive the Medal of Honor from President Richard Nixon. Lieutenant Norris, still a patient at nearby Bethesda Naval Hospital, had been forbidden by his doctors to go to the ceremony, but Thornton spirited him out the back door of the facility and took him along. Almost three years later, Norris himself received the medal, with Thornton looking on.